A Strange New Collaborator: My Thoughts on Using AI in Art

Lately, I've been spending a lot of time thinking about the tools I use in my artistic practice, and specifically, about artificial intelligence. It’s a topic that’s everywhere right now, often misunderstood. For many, AI in art is seen as a kind of magic trick—you type a few words into a box, and a finished masterpiece appears. The process is seen as effortless, and the question of who the "real" artist is becomes very blurry.

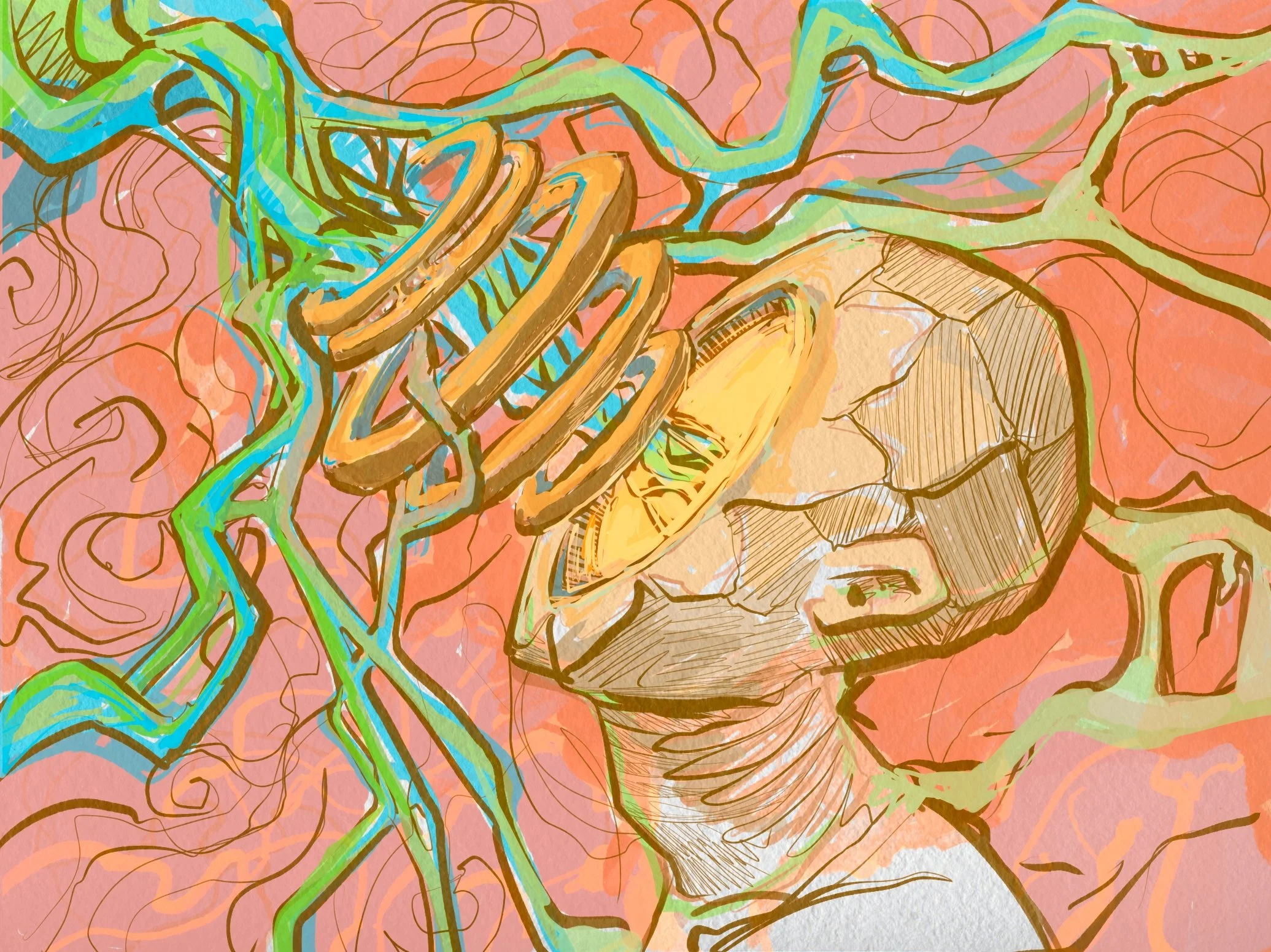

This has been on my mind as I've used AI in my own work, from generating the initial forms for sculptures like 'Spectre in the Machine' to exploring the structure of my recent poems. The process is never a simple command and response. It’s a challenging, often frustrating, dialogue. So, I wanted to share some of my thoughts on what it actually means to use AI as an artist, how I approach it, and where I believe the credit truly lies.

The Challenge: Beyond the 'Magic Button'

The first misconception to clear up is that using AI is easy. While it’s true that you can generate an image or a line of text in seconds, the vast majority of that output is generic, soulless, and creatively inert. The real challenge of working with AI is not in the generation, but in the curation and refinement. It’s an exercise in finding a single, meaningful signal in an ocean of noise.

It's a skill like any other, and I often think of it in a similar way to using a search engine. It wasn’t so long ago that the solution to any question was ‘just Google it,’ much like people now say, ‘just ask AI.’ But we all know there's a difference between a casual search and a well-executed one. The expertise is in knowing how to ask the question—what terms to use, how to structure the query, and how to interpret the results to refine your search. The same is true for AI. Getting a compelling result is a craft that depends on the user's ability to guide the tool with precise and thoughtful language.

I've found it helpful to think of the process not as an exhausting search, but as an intensive creative meeting. I'll give the AI a task or a creative brief, and in return, it will present several potential solutions. My job, as the creative director, is to evaluate these options. Sometimes one is a promising start, but more often, I find them all unsuitable. The real work then begins: providing clear, constructive feedback, refining the prompt, and asking the AI to try again with a new direction. This cycle of feedback and refinement is a deliberate process of collaboration, not a lucky search.

But the challenge goes one step further. Even after finding a compelling result, you have to hold it at a distance and ask a difficult question: Is this my voice, or the AI’s? Does the tone, the style, the vocabulary—does it truly resonate with my own artistic sensibilities, or am I just being seduced by a polished but impersonal echo?

My Process: AI as a Collaborator, Not a Creator

In my work, I've come to see AI not as a replacement for creativity, but as a strange new collaborator—one with an alien intelligence that can show me possibilities I might not have considered.

For my sculptures, I use it to generate a starting point. The form for 'Spectre in the Machine' was born from an AI, but it was just a digital seed. My work was to recognize its potential, to translate that fragile data into a physical object, to choose the materials that would give it meaning, and to build a philosophical framework around it. The AI provided a question, but the art was in the process of answering it.

For the poems, the process is a back-and-forth. I provide the core themes, the emotional direction, and the foundational lines. The AI acts as a sophisticated sounding board—a way to explore rhymes, rhythms, and word associations that I might overlook. But every final word is my own deliberate choice. I am the director, the editor, and the one who has to ensure the final piece has a soul.

The Ethical Question: Who Gets the Credit?

This brings us to the most important question: who is the author? If an AI is involved, does that diminish the artist's credit?

For me, the answer comes down to one word: intent.

An AI has no intent. It has no life experience, no joy, no suffering. It doesn't understand why it's creating something. It is a phenomenally complex mirror, reflecting the billions of human-made images and texts it was trained on, but it has no consciousness. It cannot have a "why." The artist is the person who provides the "why."

Of course, intent is only one part of the ethical puzzle. There is the deeper, more complex issue of the data these AIs are trained on—a vast library of images and texts scraped from the internet, often including copyrighted work used without the permission or compensation of the original creators.1 This is something I've had to grapple with. As an artist, using a tool potentially built on the uncredited work of others is deeply unsettling.

My approach is to ensure that my process is fundamentally transformative. I don't use the AI to mimic or replicate the style of a specific artist. Instead, I use it as I've described: to generate a strange starting point that I then take apart, rebuild, and infuse with my own intent and physical craftsmanship. My goal is for the final work to bear no resemblance to any single source, but to be a new creation that could only come from my unique process. It doesn't resolve the larger debate, but for my own practice, this principle of transformation is the ethical line I work by.

The artist is the one who sees a randomly generated shape and says, "This speaks to the idea of a digital spectre." A camera doesn't get credit for a photograph; the photographer does, because they chose the subject, the light, the frame, and the moment. The AI is a powerful new kind of camera, but the credit for the art belongs to the person who aims it, curates its output, and imbues the final result with meaning. The ghost in my machine is still very much human.