From AI Burnout to Beksiński: A Report on the Art of Feeling

This semester, one of our assignments in art school was to pick a book—any book related to our field—and write a detailed report on it. My first pick was Max Tegmark's Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence. It's a fascinating (and, frankly, terrifying) book that explores the future of humanity, superintelligence, and what happens when machines eventually outthink us.

I'd spent the whole semester focused on this topic: technology, the future of AI, and its intersection with art. And I was completely burned out.

My brain was full of algorithms, ethics, and sterile hypotheticals. I felt creatively drained, like I was losing touch with the entire reason I make art in the first place: the emotional, the expressive, the intuitive... the human part.

I needed a hard reset—a way to get grounded, get away from screens, and reconnect with something physical.

I knew exactly where to turn. Buried under a pile of art supplies, sketchbooks, and other books on my desk was Beksiński: The Art of Painting. Its immense size was the only thing giving it away. I had bought it months before, but had only briefly flipped through the paintings. Frankly, the book intimidated me. Not because of its physical heft (though it is huge), nor the amount of text—one might expect such a large volume to be full of dense writing, but it's actually mostly full-page images. No, it was intimidating because it's a book that demands focus.

You can't just casually flip through Beksiński's art; it pulls you in. The paintings are so detailed and emotionally heavy that they require you to be present, to sit with them, and to really look. It’s the complete opposite of passively scrolling through a digital feed.

And that deep, quiet focus was exactly what I needed. So, I scrapped the Life 3.0 report, pulled the massive volume out from the clutter, and turned to Zdzisław Beksiński.

Beksiński: The Art of Painting

published on December 11, 2021.

It was published by Bosz Publishing House and is available in English and Polish editions.

it’s a massive 35x27cm album, weighing over 4kg,

focusing on high-quality images.

Beksiński was a Polish painter, photographer, and sculptor who lived from 1929 until his tragic murder in 2005. He was an artist whose work I had felt a connection to, but I knew little about his story. As I've gotten to know him through this- book, especially through the writings from friends who knew him personally, that initial connection has deepened into a strong sense of kinship. They describe a quiet but generous person who always made time for friends and family; a man who didn't talk much about his feelings, but let his art express them instead. I feel much the same. Holding the Bosz album, Beksiński: The Art of Painting, became more than just an academic exercise; it felt like a journey back to the core of making art.

The book itself is curated respectfully, a product of a long-standing and positive relationship between the artist, the BOSZ Publishing House, and the Historical Museum in Sanok, where Beksiński was on good terms with both and eventually donated his entire legacy. This collaboration results in a book that mostly avoids heavy academic writing, choosing instead to use high-quality, full-page images that allow the paintings to speak for themselves. This approach is highly effective and fits with Beksiński’s well-known habit of not giving titles or explanations for his work.

He was direct about this, stating, "Meaning is meaningless to me. I do not care for symbolism and I paint what I paint without meditating on a story." He believed a painting was ultimately about beauty, and that what we see affects us as a structure of forms, colors, and lines, with the actual subject matter being secondary. This philosophy placed all importance on the viewer's own experience. As he once wrote, "doesn't matter what you saw but what you perceived. everyone perceives in a different way." The book respects this by letting the viewer connect directly with the art. However, one practical frustration is the layout; the text often discusses paintings that are pages away, requiring a distracting hunt through the massive volume, which disrupts the immersive experience the images work so hard to create. Then again, perhaps that's the point. By making it difficult to find the accompanying text, the book almost forces you to abandon the hunt for context and simply engage with the image itself—a design choice that would align perfectly with Beksiński’s philosophy.

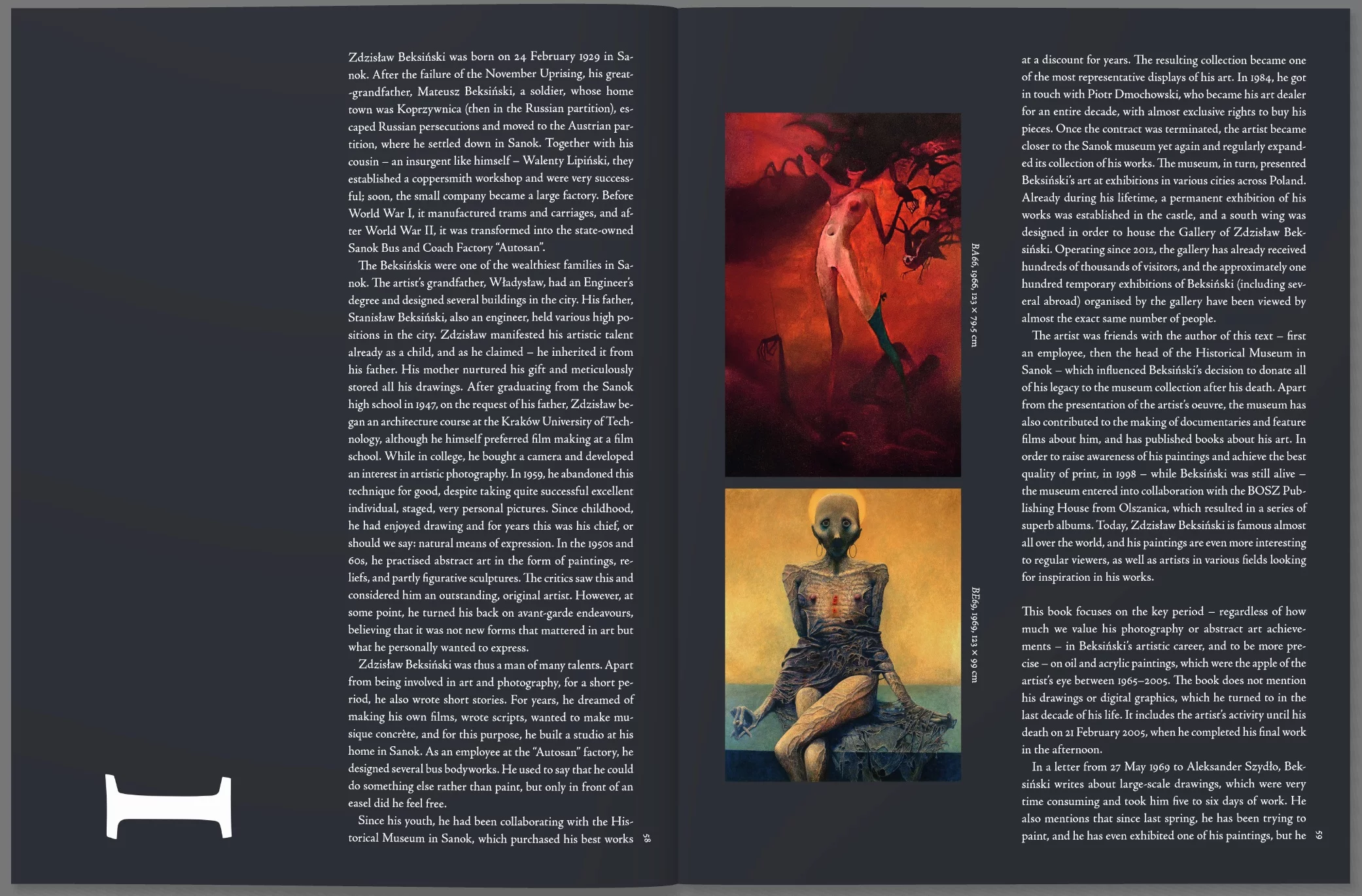

The collection of paintings in the book is gathered from the Historical Museum in Sanok, and focuses on the period in his life where he was most productive as a painter: specifically his oil and acrylic works from 1965-2005. It does not include his earlier photography, drawings, or the digital graphics he turned to later in life. What struck me immediately within this collection was the contrast between the strange subjects and the very traditional, careful way he painted. Though he always said he preferred drawing, he found that painting was the better medium for capturing the specific visions he wanted to express.

As a way to bring his love of drawing into his paintings, he developed several distinct techniques. He worked primarily with oil on hardboard, and during this time he developed three styles he named himself. The first was "hay," a technique of using very thin lines, much like a detailed sketch. This evolved into "garden hose," a method that used a much thicker line. The third was "paste," which was his term for a more traditional painting method. In some of his later works, he would combine all three techniques in a single painting, creating a rich and varied surface texture. The images in the Bosz edition are sharp enough to show these details: the very fine lines he used to paint decaying forms, the thick layers of paint on bone-like structures, and the special glazes that made his skies seem to glow with a strange light.

His use of light and shadow is very impressive. It's a dramatic style where light in his paintings never feels natural or comforting. It acts like a searchlight on a ruin or a dying sun. It doesn't make things clear; it just shows how dark everything is. His compositions feel very cinematic. While often dominated by classic, symmetrical layouts, he also used highly experimental solutions. He would use large areas of empty space, or "void," to create a sense of depth and isolation, sometimes placing a tiny head on a pole or having figures levitate in a blank, homogenous space.

Early in this period, he focused on vast, empty landscapes with monumental, ruined buildings that seem tostretch into infinity. Over time, however, figures began to take more and more focus in his paintings. This evolution feels like a slow zoom-in, from the wide shot of a dead world to the close-up of its last, lonely inhabitants. These figures are often skeletal, wrapped in blood-red bandages, or physically blended with their surroundings—lonely wanderers in a ruined world. Their shapes sometimes look like the crumbling buildings around them, suggesting they are not just in the landscape, but are a part of it, formed from the same dust and decay.

It is not my job to define Beksiński’s work; to do so would go against his entire philosophy. That said, I feel at home in his paintings. The surface themes may appear to be death and decay, but to call it simple horror would be missing the point. For me, his work captures a deep melancholy, sadness, loneliness, and dread. These are the feelings we don't like to dwell on, but that accompany all of us through life. His scenes of destruction are often quiet; it feels as though the horror has already passed, and what's left is the silent echo.

Looking at his paintings, I don't see the act of dying, but an exploration of a state of being. An image of a skeletal figure at a keyboard, or giant forms marching toward a red horizon, doesn't feel like a chaotic nightmare. It is a carefully built and constant feeling, one that is both unsettling and strangely familiar. It’s a beauty that exists not in spite of the decay, but because of it, reflecting a part of the human experience that is often left unspoken.

While the melancholy and dread were always present in Beksiński's work, knowing his personal story adds a layer of heartbreaking reality to his bleak visions. He was by all accounts a private man who disliked fame, preferring to spend his time with his family and simply paint. This private world was shattered in the late 1990s. In 1998, his wife, Zofia, passed away from a long illness. Just one year later, on Christmas Eve of 1999, his son, Tomasz—a popular music journalist and translator—took his own life. Beksiński was the one who discovered his son's body. Whether intended by the artist or projected by the viewer, one can see the impact of these events on his work that followed. The quiet desolation in his paintings feels less like a fantasy and more like a lived truth.

As an art student, I found Beksiński's approach to his craft to be one of the most valuable lessons from this book. In a world that often pushes artists to follow trends, he chose his own path, focusing entirely on what he personally needed to express. His dedication was incredible. It is particularly telling that, even as an accomplished artist, he felt a deep need to truly "learn to paint." He wrote in a 1965 letter about his plan to dedicate himself to this goal: "I want to learn, and I will be able to do this only if I work constantly for at least a month, 16 or 17 hours a day."

This relentless drive to master his craft is visible in his work. It has made me look at my own process differently and think about technique not just as a skill, but as the foundation for expressing a personal vision. His ability to control a painting's mood, for example, through his use of color—shifting between warm oranges and cold grays—is direct result of this deep commitment. It’s a powerful reminder that true artistic freedom comes not from ignoring technique, but from mastering it so completely that it becomes second nature.

Ultimately, Beksiński: The Art of Painting is more than a collection of an artist's work; it is an invitation into a complete and believable other world. The book successfully captures the immersive quality of his vision, though as noted, it focuses only on his painting work. His creative output was large, and his dedication was absolute—he reportedly completed his final painting on the afternoon of the very day he died.

Beksiński’s legacy, as shown here, isn't about providing answers. It's about his commitment to painting difficult subjects and giving shape to the feelings of dread and mystery from the subconscious mind. Leaving this book, I do not feel I have a better understanding of what his paintings mean, but I have a much deeper appreciation for what they do. They connect with us on a very basic level, reminding us that art’s greatest power is not in being explained, but in being felt.