The Fracture in the Soul: Navigating Digital Dysphoria

We are currently living through a quiet, tectonic shift in human consciousness, a transition characterized by a specific, pervasive unease known as Digital Dysphoria. This is not a sharp, sudden crisis, nor is it the dramatic "Internet Addiction" diagnosed in the early 2000s. It is something far more atmospheric: a subtle, background hum that permeates the daily experience of the modern individual. To understand it, we must revisit the philosophical concept of Dualism. Classically, this was the belief—championed most famously by René Descartes—that the human being is composed of two distinct substances: the physical, mortal body and the non-physical, eternal mind. For centuries, this was a metaphysical debate about the soul.

However, in 1949, the philosopher Gilbert Ryle attacked this concept, deriding it as the dogma of the Ghost in the Machine. He argued that treating the mind as a spectral pilot driving a biological vehicle was a category error; the mind was the body in action, inseparable and singular. Yet, the modern age has ironically resurrected the very concept Ryle sought to bury. Technology has rendered the "ghost" a practical, everyday reality. With the global average for daily screen time now exceeding six and a half hours, we are facing a staggering statistic: if maintained over an average lifespan, this amounts to roughly 22 years of pure screen interaction. Excluding sleep, this means we are spending nearly 40% of our waking lives in a digital dimension. We are forced to inhabit two conflicting modes of existence simultaneously. We have our physical presence—bound by gravity, geography, entropy, and the slow, linear march of time. And we have our digital presence—a projection that is weightless, instant, boundless, and constantly active.

Digital Dysphoria is the exhaustion of being stretched across these two divergent planes. It is the friction felt by the person who puts their phone down to enjoy a sunset, only to feel a nagging, subconscious urge to capture it, filter it, and share it. The dysphoria arises from the realization that the moment feels incomplete until the "ghost" has processed what the "machine" has seen. The biological eye sees the light, but the digital self must verify its existence. This gap creates a profound ontological nausea, a sense that we are living in a dull waiting room (the physical world) while our "real" lives happen on the illuminated screen.

The primary engine driving this friction is Algorithmic Curation, which has fundamentally altered how we perceive value. Social media functions as a "highlight reel" of the real world, creating a state of Hyperreality—a term coined by philosopher Jean Baudrillard to describe a simulation that feels more vibrant, more coherent, and more "true" than the chaotic reality it simulates. The online world offers a cleaner, more responsive version of social interaction than the physical one. This has measurable consequences. Leaked internal research from Meta (formerly Facebook) in 2021 revealed that Instagram made body image issues worse for one in three teen girls. This is not just "feeling bad"; it is a quantified dysphoria where the physical self is judged against an algorithmic standard and found wanting.

This creates a stark inequality between our two selves. The digital self has a score (likes, views); the physical self does not. The dysphoria creeps in when we return to the "messiness" of physical life—the commute, the waiting in line at the grocery store, the unedited face in the bathroom mirror—and find it essentially limited compared to the instant connectivity of the feed. We are becoming quietly disappointed by reality's lack of perfection. We begin to view our physical lives as merely the "raw footage"—dull, unlit, and unstructured—that must be edited, color-graded, and uploaded to become valuable. The act of living becomes secondary to the act of broadcasting.

This sense of inadequacy is being deepened into a crisis of identity by the rapid integration of Artificial Intelligence and Synthetic Media. As we move from the era of curation to the era of Generative Creation, tools like neural filters are becoming standard. Take, for instance, TikTok’s "Bold Glamour" filter. Unlike previous generations of filters that merely overlaid a mask, Bold Glamour uses machine learning to re-mesh the user’s face in real-time, creating a seamless, undetectable upgrade to bone structure and skin texture. This creates an Inverted Uncanny Valley. Traditionally, the "Uncanny Valley" referred to robots that looked creepy because they were almost human. Today, the dynamic has flipped: AI-generated faces look so symmetrical, lucid, and mathematically perfect that actual human faces begin to look wrong by comparison.

This introduces the Synthetic Ideal—a standard of appearance and efficiency that is biologically impossible to achieve. We see this in the rise of AI influencers like Aitana Lopez, a purely synthetic model who earns thousands of dollars a month, effectively replacing human labor with a being that never sleeps, never ages, and never complains. When we are bombarded by images of a reality that is brighter, sharper, and more consistent than the one we see with our own eyes, the "truth" of the physical world erodes. This manifests as a mild, constant pressure: the feeling that our biological body is slightly outdated, a heavy vessel that cannot quite keep up with the pristine clarity of the digital tools we use every day.

A Instagram post by the Ai influncer Aitana Lopez.

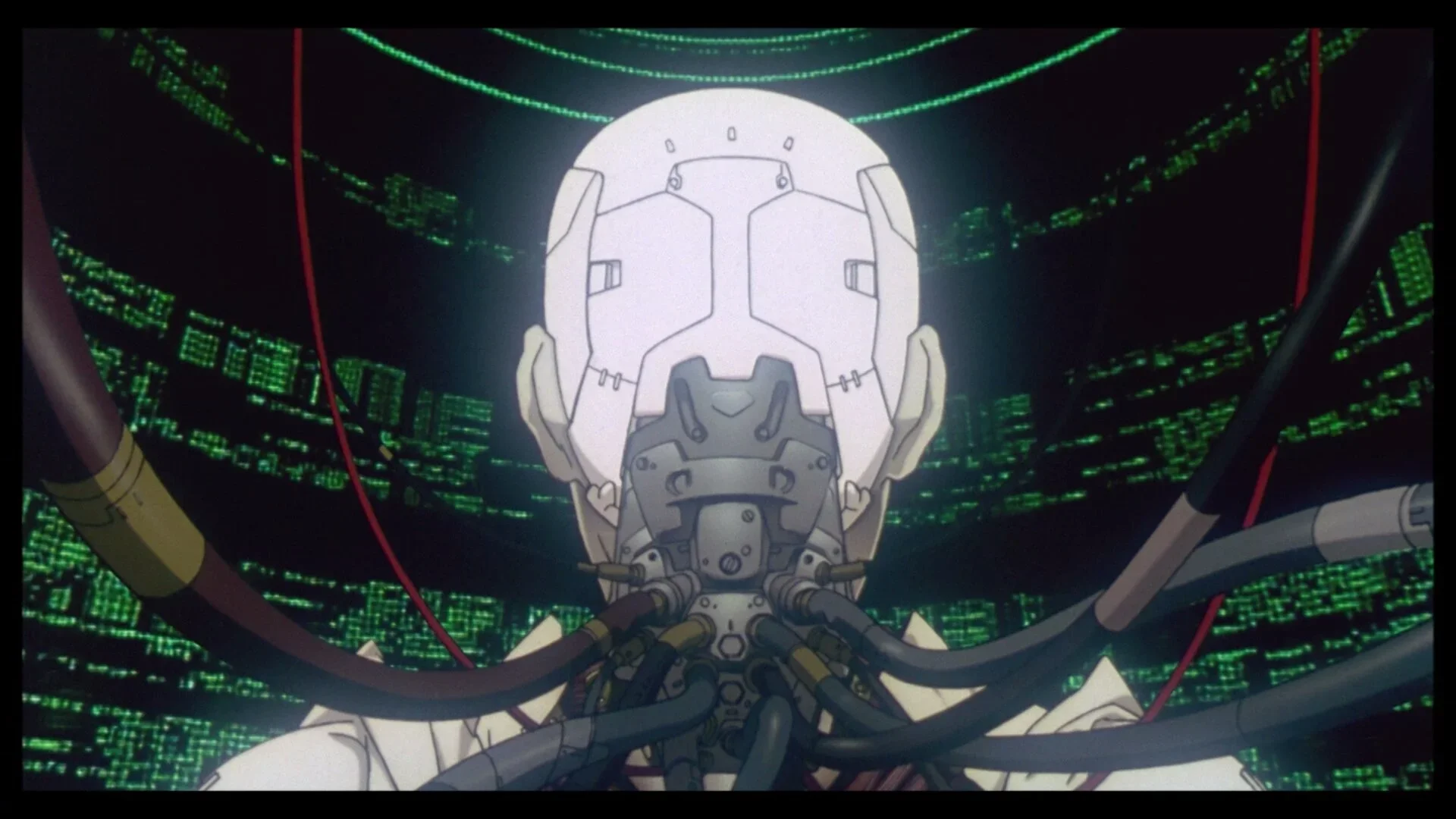

The logical extrapolation of this impatience is found in the philosophy of Transhumanism, a movement that finds its cultural touchstone in the cyberpunk classic Ghost in the Shell. The work reanimates Ryle’s terminology, transforming the "Ghost in the Machine" from a critique of dualism into a prophecy of our future. Transhumanism posits that Digital Dysphoria is not a disorder, but a valid critique of our limits. It frames the frustration we feel—the back pain, the brain fog, the inability to be in two places at once—as a problem to be solved.

This leads to the pursuit of Morphological Freedom, the right to modify the "shell" to match the speed and capability of the "ghost." We see this in the booming "Quantified Self" industry—a market projected to reach hundreds of billions of dollars—where millions of users rely on wearables to audit their biological performance. We track sleep, heart rate variability, and blood oxygen levels, treating the body not as a home, but as a platform to be patched. Transhumanism offers a seductive answer to the friction of modern life: instead of slowing down our digital consumption to match our biology, we must enhance our biology to handle the speed of the digital.

However, this merge is becoming more psychological than physical, and this is where the danger lies. We are entering a phase of deep Reciprocal Shaping with Artificial Intelligence. We tend to think of AI as a tool we control, but as millions of people spend hours daily conversing with chatbots, the dynamic shifts. A study dubbed the "Google Effect" (or digital amnesia) has already shown that humans are less likely to remember information they know can be retrieved digitally. Now, we are outsourcing emotional labor as well. Apps like Replika, which offers AI companions, have amassed millions of users who form deep, romantic, or therapeutic bonds with algorithms.

This atrophy extends beyond memory and into the very architecture of our social development. As Swedish psychologist Anders Hansen points out in his work Skärmhjärnan (The Screen Brain), the tragedy of excessive screen time—especially for children—is not merely the physiological toll of disrupted sleep, prolonged inactivity, and the rewiring of attention spans, but the displacement of physical reality. A child spending six hours a day staring into a screen is spending six hours not learning to read micro-expressions, not navigating the awkward friction of physical play, and not developing the resilience required for real-world interaction. We are effectively trading the complex, messy training ground of the physical world for a streamlined digital nursery. We are raising a generation fluent in interfaces but illiterate in intimacy.

Ghost in the Shell (1995): The scene that inspired The Matrix.

We must ask: are we training the AI, or is the AI training us to think in prompts? As we simplify our language to be machine-readable, and as the machine becomes our primary confidant, we risk becoming transfixed by the system, blinded to the fact that our own cognitive muscles are atrophying from disuse. This leads us toward a perilous horizon where the distinction between human and machine becomes irrelevant. In a few years, when the voice in the chat is indistinguishable from—or perhaps more empathetic and intelligent than—a biological human, the concept of "authenticity" collapses. If the digital entity provides better companionship and more efficient labor than a person, the necessity of the biological human in the digital space evaporates.

This brings us to the ultimate trap: Posthumanism. While Transhumanism focuses on enhancing the individual shell, Posthumanism—much like the ending of Ghost in the Shell—questions the value of the "individual" entirely. It implies that the autonomous person—the "I" that we protect so fiercely—is an obsolete historical construct. In a posthuman view, we become Networked Subjects, defined less by our bodies and more by our connections. We glimpse this future in moments of total immersion, where the relief of disappearing into a game or a stream makes physical identity dissolve completely.

The seductive danger of this path is that it frames Digital Dysphoria as a sickness to be cured by surrender. It encourages us to stop fighting the current and dissolve into the network. But we must critique this impulse. Digital Dysphoria is not a glitch; it is a vital warning signal. It is the pain of the human spirit resisting its own deletion. The discomfort we feel is the friction of our humanity rubbing against a system designed to strip it away. If we simply merge with the machine to escape the pain, we lose the very thing that gives us perspective: the messy, slow, vulnerable "shell" that anchors us to reality. The challenge of our time is not to transcend the body, but to reclaim it—to remain vividly, stubbornly human in a world that wants us to be data.